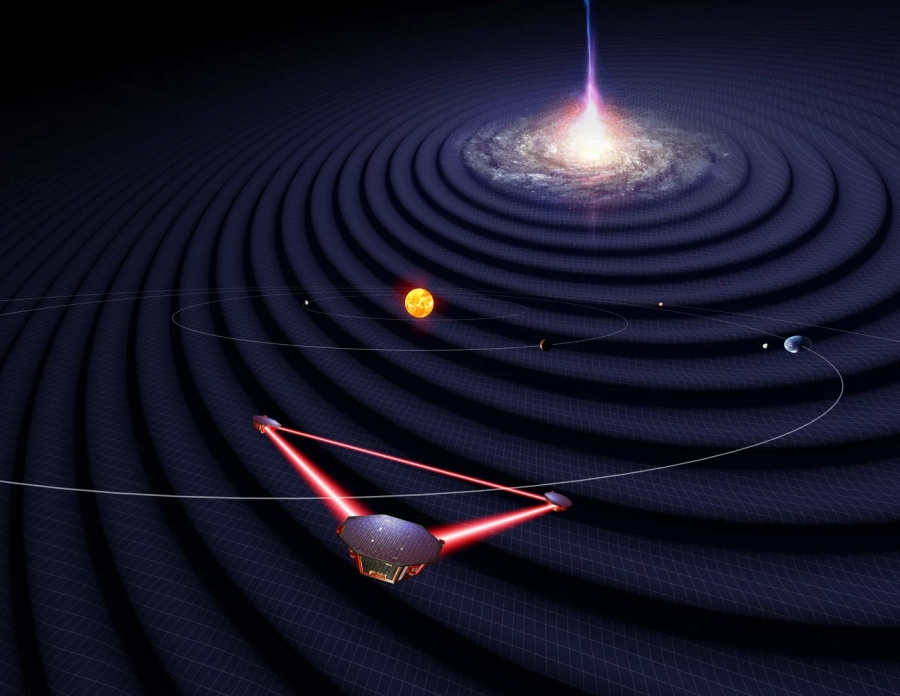

So far, we have been searching for gravitational wave signals with our ground -based detectors (the LIGO-Virgo). Since 2016, the searches have been a tremendous success, revealing a “ton” of signals that give us an abundance of information about our universe. These signals have already expanded our knowledge about astrophysics, astronomy, and fundamental physics, but in order to have a more complete picture, we need to measure gravitational waves in in the lower part of the spectrum. We need to measure the merger of really heavy objects, like supermassive black-hole behemoths, and to do that, we need to build a detector in space. This is where LISA comes into play, the next space-based gravitational wave detector. LISA stands for Laser Interferometer Space Antenna, and is basically a set of interferometers in space. When built, it will be the largest man-made structure to date, because each spacecraft of the constellation will be separated by 2.5 million kms!

Each space craft will host a pair of cubic test-masses, that are going to be floating freely inside their respective caging. Their relative distance between the other two far-away space crafts, will be constantly monitored with laser beams. A passing gravitational wave will stretch and expand their relative distance, and we will be able to capture this motion.

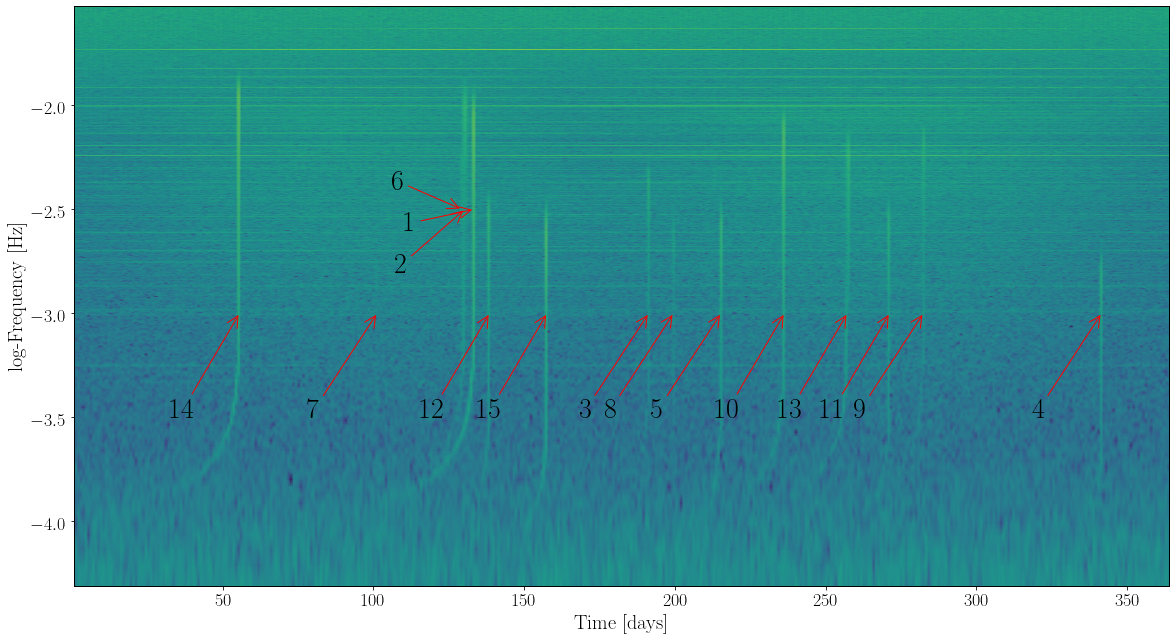

Contrary to ground-based detectors, when we switch LISA on we will measure gravitational wave signals coming form all types of sources simultaneously. That means that LISA is going to be a signal dominated observatory!

Example of a simplified measurement of LISA (Source). Millions of Compact Galactic Binaries (mostly White Dwarf binaries), and Supermassive Black Hole Binaries. The y axis represents the power in the TDI X channel output, while on the x-axis the frequencies are shown. TDI stands for Time Delayed Interferometry, and it is the trick we have to do in order to make those demanding measurements in space (More details can be found here).

While this is very exciting, it also creates a problem for us: the problem of source separation. We need to develop efficient data analysis algorithms that will allow us to dig into this complicated data set and extract the science. This is challenging, but the LISA Consortium has gathered more than 1000 people working on the development of the mission, a great portion of them devoted to overcoming data analysis challenges.

Here in Thessaloniki, the local Gravitational-Wave group contributes to this effort as well. In the future I will be posting more details of this work, and I hope that people will find it interesting!